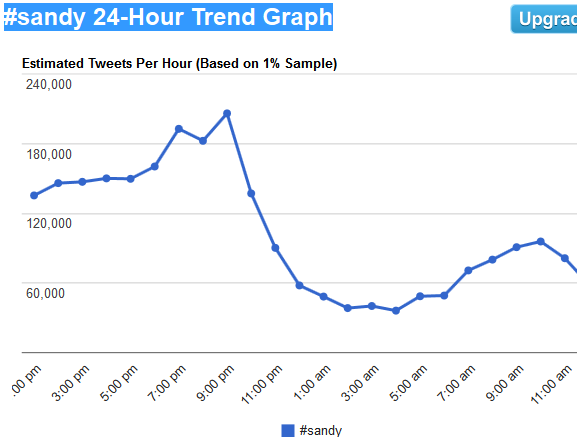

The response to tropical storm/hurricane Sandy online has been remarkable. There’s little anyone else is talking about, and even as far off as the Middle East people are sending their wishes to those caught in the storm’s path. To give you an idea about how Sandy has been trending on social media, have a look at the analytics graph from Hashtag.org for #sandy.

The graph, from hashtags.org, is from a one percent sample of Twitter traffic over the past 24 hours.

Everyone has been pitching in to provide help, support and comfort to those affected. According to thenextweb, Twitter has supported relief efforts by promoting the following twitter accounts @RedCross, @FEMA,@NYCMayorsOffice, and @MDMEMA. “Twitter is also listing government accounts and resources on its blog and giving #Sandy a custom page,” according to the piece by Harrison Weber on TNW.

Even celebrities have been taking to the social media space to talk about Sandy.

https://twitter.com/ABFalecbaldwin/status/263245395025600512Aside from the danger to life posed by Sandy, the main talking points have been flooding and power outages. As a big fan of the likes of ABB (my former company) and GE, I was hoping that they and others would be talking about the disaster and lending a hand to get everything back on track. Estimations are that eight million people are without power right now in the Eastern seaboard of the US, and that utility company staffers are traveling from as far as California and Texas to help out in New York.

And what is on GE’s Facebook page?

This was GE’s latest post to their Facebook page, which is liked by over 900,000 people. There’s no mention of Sandy.

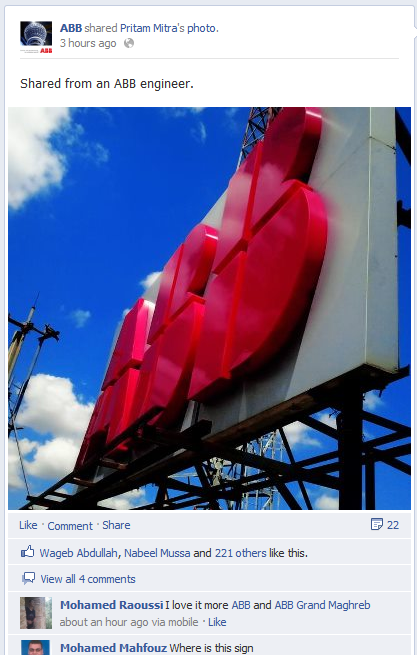

And ABB?

ABB’s latest Facebook post which was put up in the afternoon of October 30. Again, no mention of Sandy.

This isn’t exactly an empirical study, but it worries me that two of the world’s most respected electrical engineering companies are not lending their support or even making their support known by social media. While I understand that many corporates don’t want to be seen to be taking advantage of the situation, surely there’s a time and place for them to offer their support and advice publicly.

Not talking about what is affecting millions of people seems so out of place, especially when on social media and when the companies mentioned provide solutions that power our utilities.

After all, aren’t we supposed to be talking with each other via Facebook and Twitter. Or do we go on, ignoring global events? Hardly being socially responsibly on social media, is it?

![The Best Time To Tweet [INFOGRAPHIC]](https://alexofarabia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/the-best-time-to-tweet-infographic.png?w=584)